Another key difference between a lawsuit and mediation is how the neutral is selected.

In a lawsuit, judges are elected to office by voters, and once on the bench, cases are assigned by the clerk’s office through an impartial process the parties do not control. Similarly, as many of us have seen on Boston Legal, CSI, A Few Good Men, or some other lawyer-like shows, litigants really have very little control over who serves on a jury. It may be that the lawsuit involves a very novel or complex set of facts, or technology, or emotional issues – issues that the randomly-assigned decisionmakers – judges or prospective jurors – may have little or, sometimes, no prior experience with.

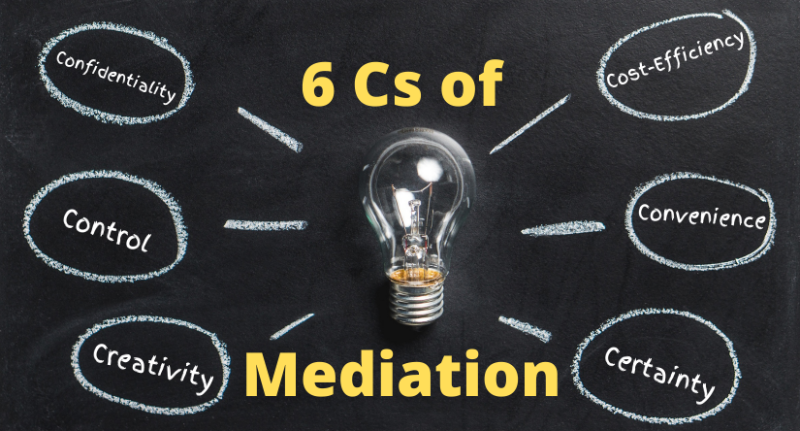

By contrast, when parties agree to mediate, not only do they get to select the mediator, the parties, their counsel, and the mediator will work together as active participants in the mediation process. The goal of the mediator is to help the parties — the only decisionmakers in a mediation – to evaluate and decide how they want to end their conflict.

While mediators may also be lawyers, mediators do not give legal advice or make any decisions. Instead, a mediator’s role is to encourage the parties – with the guidance and input from their lawyers – to consider ways they can resolve their dispute. When the parties feel stuck, a mediator may ask questions or make suggestions to help them evaluate their case or brainstorm ways to bridge their differences and find common ground for a resolution.

What can happen at the end of a trial, and what can happen at the end of a mediation, are also two things to be mindful of.

At the end of a trial, the judge or jury will reach a verdict, decisions upon which the court will then enter judgment. Once the judgment is entered, if one party (or both) do not like the judgment, they each have a right to at least one appeal. In essence, the trial judge or jury’s decision may not be the final say.

When successful, mediation ends with a written settlement agreement, which is intended to bring an end to the dispute. In fact, sometimes parties are able to resolve their dispute in a mediation that occurs even before a lawsuit is filed.

If mediation is not successful, a mediator will let the parties know that they are at an impasse, after which the parties are at liberty to continue efforts to resolve their disputes through the court system.

If an impasse occurs that does not mean the mediation was a waste of time. Often, even when the parties are not able to completely resolve their dispute in mediation, they find the mediation process assisted them in narrowing the issues, or at least getting a better handle on the strengths and weaknesses of their respective cases. This insight often leaves open the parties’ interest in continued negotiations in the future.

Most mediators know this and will stay in touch with the parties’ counsel by checking in periodically and offer to assist the parties either with another mediation session, or through informal measures, such as telephone calls and emails.

How quickly a dispute can be resolved through litigation and mediation is a difference that can be measured in time and money.

It’s not uncommon for parties to wait several years before a lawsuit is tried. During the period of time leading up to trial, the lawyers, witnesses, and others will usually spend considerable time and money collecting and evaluating evidence, witnesses, and positions. The whole process can be quite expensive, stressful, and distracting to one’s daily schedule.

By contrast, many disputes have been resolved (as discussed above) through a concentrated and focused effort to meaningfully negotiate over the course of a half- or full-day’s time. The cost of the mediator, and the investment of a few days or weeks preparing for mediation, can be significantly appealing to some litigants.

So whether or not to mediate or file a lawsuit first, when to mediate if a lawsuit is filed, and who to enlist to serve a the neutral mediator are among the things parties, with the assistance of their counsel, consider when evaluating one’s dispute resolution options.